Werner Erhard and Victor Gioscia, San Francisco, Calif.

From Biosciences Communication 3:104-122, 1977

Abstract. The format of the est training is described.

Relationships which participants develop in the training are: to the

trainer, to the group, and to self. Three aspects of self are presented:

self as concept, self as experience and self as self. Relation of these

three aspects of self to the epistemology of The est Training are discussed, as are

the experiences of aliveness and responsibility.

Introduction

Since fundamentally, est is a context in which to hold one's experience,

I want to begin this essay by thanking a number of people for providing

me with a context in which to write it. To begin, I want to thank those

who attended the panel discussion at the APA meetings in May 1976,

and, in addition, I want to thank the reader for this opportunity to

discuss the est Training.

In the paragraphs that follow, I will present some information which

may be useful as a context in which to examine est as an example of

an 'awareness training' in relation to contemporary psychiatry. I want

to say at the outset that I am not qualified to write about large scale

awareness trainings in general, and I will not presume to tell you

anything about psychiatry. What I want to do is share with you some

of the format, intended results, and 'theory' of est as an example of a

large-scale awareness training.

My intention is to provide a context in which the reader can have something of an experience of est and to create an opportunity for the

reader, not simply to have some new concepts but to have an

experience of what est is, insofar as that is possible in an essay.

So, I want the reader to know that my ultimate purpose is not to tell

you some facts you did not know. I do ask you to entertain the

possibility that there is something you do know, which you have not

been aware that you know. The est training is an opportunity to

become aware that you know things you did not know you knew, so it

is not a 'training' in the usual 'rule-learning' sense of the word, nor is it

an ingraining, by repetition or any other means, of behaviors, attitudes

or beliefs.

Fundamentally, then the est training is an occasion in which

participants have an experience, uniquely their own, in a situation

which enables and encourages them to do that fully and responsibly.

I am suggesting that the best way to learn about est is to look into

yourself, because whatever est is about is in your self. There are some

who think that I have discovered something that other people ought to

know. That is not so. What I have discovered is that people know

things that they do not know that they know, the knowing of which

can nurture them and satisfy them and allow them to experience an

expanded sense of aliveness in their lives. The training is an occasion

for them to have that experience - to get in touch with what they

actually already know but are not really aware of.

Format

The est Training is designed to be approximately 60 hours long. It

is usually done on two successive weekends - two Saturdays and two

Sundays -beginning at 9 a.m. and going until around midnight.

Sometimes a day's session takes longer, sometimes a little less, since

the sessions go until the results for that day are produced.

There are breaks about every 4 hours for people to go to the bathroom,

have a cigarette, talk, or do whatever they like. In addition, there is

one break for a meal during the day. People usually eat breakfast

before and dinner after if they are less tired than hungry. We have

altered these times on occasion to adapt, for instance, to institutional

schedules. The same results have been produced doing the training

over ten weekday evening sessions of 6 hours each with a break in the

middle of each session, and over three consecutive weekend sessions

of 10 hours each with three breaks including a meal break. The point is

there is nothing in the duration of the training that is intrinsic to the

training.

Included in the tuition, in addition to the two

weekends, are three optional seminars, called the pre-training, the

mid-training, and the post-training seminars. These are approximately 3

hours long, and are conducted in the evenings a few days before, between

and a few days after the weekend training sessions.

The est training is held for about 250 people at a time, who are seated on

chairs, arranged theater style, in a hotel ballroom. The trainer stands

on a low platform in the front of the room so that the trainer can see

and be seen by everyone. There are support personnel who sit in the

back of the room, who manage the logistics of the training. For

instance, they inform those participants on medication (who sit in the

back row), when it is time to take it. There are microphones, to

facilitate people who want to say something or ask a question, and

everyone wears a nametag so that the trainer can address people by

name.

Sometimes people wonder about what might be called the harshness of

the training - why the rules are so unbending. It became very clear to

me about 5 years ago that the rules in life do not bend. In other words,

if I fall down, gravity does not say 'Well, we're going to relax the rules a

bit since you hurt yourself . I think that it is important for people who

are being given an opportunity to discover themselves, to discover for

themselves that there are stable environments, certain facts of living,

they cannot 'con' or persuade into changing for them, no matter how

pitiable they are, and no matter how intelligent and dominant they are.

So the people who handle the supervision of the training - the room, the

number of chairs, etc. - have been trained to be very consistent - to go

by the book. The purpose of going by the book is not that we think you

ought to go by the book all the time - that kind of rigidity in a person is

obviously a mistake. It is to accentuate that the physical universe

always goes by the book and that, like gravity, life does not relax the

rules just because you want it to or even because you need it to.

Gravity does not care, you see. It simply is. At the same time, the

training is conducted with love and compassion (not sympathy and

agreement) and anyone who completes the training is clear in their

experience of this love and compassion. They know that their true

power and dignity has been recognized from the very beginning of the

training.

There are three relationships which develop during the course of the

training which provide a framework for the material of the training.

One is a relationship with the trainer, who begins the training with what

resembles a lecture, although trainees soon realize that it is not

actually a lecture. To be sure, the trainer stands in front of the room

talking, but he says things like 'If you experience something completely,

it disappears', and since he says that early on in the training, almost

everybody thinks that it is not true. Some people reinterpret it to mean

something else like that, but not quite that, which could be true for

them. In other words, people begin to develop a relationship to the

trainer, who presents certain data about experiencing life, which

trainees can examine to see if what he is saying is true for them in their

experience. There may be a give and take between the participants

and the trainer for a while until everyone is very clear what the trainer

said. That does not mean anyone has accepted it. In fact, people are

effectively cautioned against merely believing anything presented in the

training. It just means everyone knows that is what the trainer said, and

everyone begins to develop his or her own unique relationship with the

material the trainer presents, by seeing the unique relevance of what

the trainer has to say in relation to his or her own beliefs about and/or experience

of living.

Another relationship which develops in the est training is the trainee's

relation to the group and to the individual members of the group. This

develops out of an aspect of the training we call sharing, by which we

simply mean telling others what is going on in the realm of your own

experience. Initially, people raise their hands, one of the support people

brings them a microphone, and they talk about something - be it an

annoyance, or an insight, or their theory of the training, etc. Then, as

the training goes on, people begin to share more fully what they are

actually experiencing, until, toward the end of the training, people

become able to share in a way we call 'getting off it' - relating things

they have held on to perhaps for their entire lives - things they have

been stuck with yet were unable to reveal they were holding on to, and

now find they can let go of. About a quarter of the people in a given

training share meaningful things of this sort. The rest either do not

share or say conceptual kinds of things.

There is no confrontation from the group to a trainee or from the

trainer to a trainee except in rare instances by the trainer. We ask

trainees not to evaluate, judge or analyze each other's sharing, not to

engage in a dialogue with each other, and on that basis to say

whatever they have to say to the trainer, so that the training can

occur within each individual's own experience, rather than in others'

concepts or in the dynamics of the group. Those who choose to share,

do so, and those who choose not to, find it is not required to realize

the results of the training.

When people share, other trainees often find they can see their own

story more vividly in someone else's experience than they can in their

own. So a large part of the value people get in the training is the view

they see of themselves in others' sharing.

The third relationship people experience in the training is an enhanced

relationship to themselves, which in part, occurs during what we call

processes. These are techniques in which people switch their attention

from seeing their concepts about themselves, others and life, to

observing directly their experience of themselves, others and life. This

is done in an environment - or 'space' - that is safe enough for them to

do that. That is, in a safe space, there is no expectation that you

prove anything, or demonstrate anything, or keep up any appearances.

In a safe space, whatever is so is not used to justify or explain or be

consistent with a point of view. Processes are simply an occasion to

look directly into one's experience and observe what's going on there,

in safety.

For example, there is a process in which people are asked to select a

problem from among those they have in life and to see specifically

which experiences are associated with that problem - which body

sensations in which specific locations in the body, which emotions or

feelings, which attitudes, states of mind, mental states or points of

view, which postures, ways of holding themselves, gestures, ways of

moving, habitual actions and countenances, which thoughts,

evaluations, judgments, things they have been told or read,

conclusions, reasons, explanations and decisions, and which scenes

from the past are associated with that problem. People discover

remarkable things about their problems - for instance that there are

body sensations felt when and only when that problem intrudes into

their lives - a fact they had not noticed before.

Some processes last for 20 min, others for 90 min. People are usually

seated during them, and afterwards they are invited to communicate

whatever insights or awareness they had. Ina very real sense, then,

the trainees literally create the training for themselves.

People think there is an est training, when in fact, there is not. There

are actually as many trainings going on in each training as there are

individuals in the training, because people actually 'train' themselves, by

handling on an individual basis those aspects of living that are common

to all of our lives. Each part of the training becomes real for

participants by virtue of experiencing themselves, not concepts derived

from someone else's experience.

Thus, the est training is not like a classroom in which the aim is to agree or

disagree with a concept or a theory. In the training, we present

spaces, or contexts, or opportunities, in a way that allows people to

discover what their actual experience is. Participants in the training

report and give evidence of obtaining value from getting beneath their

concepts, their points of view, their unexamined assumptions,

explanations, and justifications, to the actual experience of themselves,

others and life.

To know oneself, as Socrates suggested, does not seem to provide the

experience of satisfaction - of being whole and complete if one knows

oneself in the same way as one knows about things. Thus one can

know about love and not know love, just as one can know all the

concepts of bicycle riding without having the experience or the ability

to actually ride a bicycle. The training is about the experience of love,

the ability to love and the ability to experience being loved, not the

concept or story of it - and it is about the experience of happiness,

and the ability to be happy and share happiness, not the concept, story or symbols of it. In short, the training is about who we are, not

what we do, or what we have, or what we do not do or do not have. It

is about the self as the self, not merely the story or symbols of self.

People often ask if the training is something one needs. The training is

not something one needs. Now this statement is usually met, if not by

surprise, then with outright disbelief. For, if the training is not

something one needs, why should one do it.

The fact is, people usually come to introductory seminars when they

see that their friends or family or associates who went to the training

experienced a transformation or enlightenment which they themselves

would like to experience. It is a natural part of the experience of

transformation to share the opportunity to have the experience of

transformation with others.

This becomes amusing after the people who had the hardest time

understanding why their friends or loved ones were so excited and

enthusiastic and eager for them to know about the training, finally do

take the training, they then meet the same bewilderment in their

friends and loved ones when they try to share it, because now their

friends insist they do not need it either.

The fact is, no one needs the training. It is not medicine. If you are ill,

you need medical attention. If you are mentally ill, you need therapy.

The training is not medicine or therapy. If you are hungry, you need

food. You need air. Actually you need someone to love and someone to

love you. You need to feel some self-respect and the esteem of others.

Without these, we do not function very well as human beings.

The training is none of these. It does not solve problems. It is true that

some problems dissolve in the training, but not because it is the

purpose of the training for people to work on their problems in the

training. The training is not about people's problems per se.

What the training is about is related to those rare moments in life,

which while rare, seem to come into everyone's life at some time or

another. They are moments in which one is absolutely complete, whole,

fulfilled - that is to say, satisfied. (I limit the word gratification to mean

the filling of a need or desire, or the achievement of a goal. I use the

word satisfaction to mean the experience of being complete.)

Each of us has experienced moments in our lives when we are fully alive

-when we know - without thinking - that life is exactly as it is in this

moment. In such moments, we have no wish for it to be different, or

better, or more. We have no disappointment, no comparison with ideals,

no sense that it is not what we worked for. We feel no protective or

defensive urge - and have no desire to hold on - to store up - or to

save. Such moments are perfect in themselves. We experience them as

being complete.

We do not need to experience completion. People function successfully

without such moments. Like the training, such moments are not

something we `should' have. Like the training, such moments do not

make us any better. We are not smarter or sexier or more successful or

richer or any more clever. These moments, these experiences of being

complete, are sufficient unto themselves. Like the training, such

moments are not even 'good' for you - like vitamins or exercise or

things of that sort.

In the training, one finds there is something beyond that - the opportunity to discover that space within yourself where such moments

originate, actually where you and life originate. In the training, one

experiences a transformation -a shift from being a character in the

story of life to being the space in which the story occurs - the

playwright creating the play, as it were, consciously, freely, and

completely.

Because the experience of being complete is a state change from the

rest of life, the questions and instruments we usually apply to measure

life do not apply. We shall need to develop a whole new set of

questions - a new paradigm to approach the experience of being

complete.

In the training, the experience of being at the effect of life - of having

been put here, and having to suffer the circumstances of life, of being

the bearer or victim of life, or at best, of succeeding or winning out

over the burdens of life -shifts to an experience of originating life the

way it is - creating your experience as you live it - in a space uniquely

your own.

In that space, the problems of life take on an entirely different

significance. They literally pale, that is, become lighter - or enlightened.

One sees, quite sharply, that who one is simply transcends and

contextualizes the content with which one has been concerned. The

living of life begins to be what counts, the zest or vivacity with which

one lives, what matters.

It has been said that this is a polyanna view - that I think there's no

pain and suffering in life. That is not my view at all. There is no doubt

whatsoever in my experience and observation that people do suffer,

that there is pain in life. If we were to sit quietly in an empty room for

a few minutes looking at what we do and how we live, and at how

much time we spend doing things that we pretend are important to us,

most of us would find that we spend more time pretending not to suffer

than in creating the experience of our lives.

In my observation of life, I find that during most of the time we are

interacting with others, we are pretending, and we get so proficient at

pretending that we eventually no longer even notice that we are

pretending. We become 'unconscious' of pretending. We forget that the

actual experience of loving someone - in contrast to the pretense or

concept of loving someone, or the 'act' or drama of loving someone -

leaves one absolutely high, vivacious, and alive.

Yet, each of us behaves as if we were really three people. First, there

is the one we pretend to be. No one escapes this. Every one of us has

an act - a front - a facade - a mask we wear in the world that tells the

world who we are pretending to be. We think we need this to get along

in life and be successful.

Underneath that mask is the person we are afraid we are - the person

who thinks those small, nasty, brutish thoughts we try to hide, because

we think we are the only one who thinks them, until we are willing to

accept that we do actually think them, and only then notice everyone

else does too. Until we confront our own smallness, we do not

experience our real size. The truth is, we can only be as high as we can

confront and take responsibility for being low.

I am suggesting that it is useful from time to time to get in touch with

why it is we have to be intelligent or successful or wonderful or kind. I

am suggesting that when we look underneath the facade we present,

we will find a cluster of thoughts, emotions, attitudes, etc. which are

the exact opposite to what we have presented. All of us who are given

credit for being intelligent have feelings, thoughts, etc. of stupidity and

ignorance. All of us who are given credit for being wonderful have

doubts. In my observation (which includes a fairly intimate interaction

with over 90,000 people) we all have doubts about the authenticity of

the way we present ourselves in the world.

Some people find this idea annoying. If you have spent your whole life

proving you are not a fool, it is annoying to be called a fool. (A fool is

one caught in his own pretense.) We are all very careful not to make

fools of ourselves or not be fooled. Many see it as the ultimate

disgrace. Only a fool pretending not to be a fool would be afraid of

making a fool of himself. A fool presenting himself as a fool would have

no problem with it, just as one who knows he is not a fool would have

no problem making a fool of himself. Similarly, a man secure in his

masculinity has no problem expressing feminine qualities. Each time we

try to prove we are not fools we reinforce the belief that we must

prove that we are not.

Underneath these two 'selves' - the 'front' and the 'hidden' - is the one

we really are - under the one we work at being, the one we try to be,

the one we are pretending to be, and underneath the one we do not

want to be, the one we are avoiding being, and the one we fear we

are. The extent to which we can allow ourselves to confront - to

experience and be responsible for - the pretense and trying, the

avoidance and fear, is the extent to which we can be who we really

are.

The experience of being yourself is innately satisfying. If who you really

are does not give you the experience of health, happiness, love and full

self-expression - or 'aliveness' - then that is not who you really are.

When you experience yourself as yourself, that experience is innately

satisfying. The experience of the self as the self is the experience of

satisfaction. Nothing more, nothing less.

Satisfaction is not 'out there'. It cannot be brought in. You will never

get satisfied. It cannot be done. When you want more and different or

better, that is gratification, and while that is gratifying, we always

want even more or even better. Satisfaction is completion, being

complete - what has been called 'the peace that passeth all

understanding'. It is a condition of well-being - a sense of wholeness

and of being complete right now - a context of certainty that right now

is completely all right as right now and that the next moment will

similarly be, fully itself. Not a judgment of good or bad, right or wrong,

just what is.

I do not refer to smugness or to naivete, or to a preoccupation with

self achieved by shutting out the world. I do not mean narcissism. I

refer to the quality of participation which generates enthusiasm in its

performance and in its beholders. I refer to the kind of invigorating

vitality that makes a difference in the world. Most of those who explain

what we ought to do in the world do not make a difference in the

world.

To summarize what happens in the est training, then, I would say the

following. It is a transformation - a contextual shift from a state in

which the content in your life is organized around the attempt to get

satisfied or to survive - to attain satisfaction - or to protect or hold on

to what you have got - to an experience of being satisfied, right now,

and organizing the content of your life as an expression, manifestation

and sharing of the experience of being satisfied, of being whole and

complete, now. One is aware of that part of oneself which experiences

satisfaction - the self itself, whole, complete, and entire.

The natural state of the self is satisfaction.

You do not have to get there. You cannot get there. You have only to

'realize' your self, and, as you do, you are satisfied. Then it is natural

and spontaneous to express that in life and share that opportunity with

others.

This explains, I think, the fact that people from all walks of life take the

training, so that, with the exception that the group of graduates

includes a higher percentage than the average population of better

educated people and therefore the group also includes a higher

percentage than usual of professionals, they are representative of the

community at large. I say 'explains' with tongue in cheek of course, for

by now you will have perceived that the only quality one must have to

'get' the est training is self.

So everyone 'gets' it, that is, has an experience of self as self. A few

'desist' because they have patterns of resistance that they are now

completing (rather than dramatizing or reinforcing) as a part of

expressing their being complete. Some do not 'like' it, others delay their

acceptance, both also patterns now to be completed. Even these, in

my experience, have it, and are covering it over, for a while, with

considerations, explanations, or other contents which they are

completing.

This is not a matter of concern to us, since the principal intended result

of the est training is a shift in the person's relationship to their system

of knowing contents, or technically a shift in their epistemology. Thus,

the contents of people's lives are not worked on per se during the

training, since it is not the purpose of the training to alter the

circumstances of lives or to alter peoples' attitudes or point(s) of view

about the circumstances of their lives. It is the purpose of the training

to allow people to see that the circumstances of their lives and that

their attitudes about the circumstances of their lives exist in a context

or a system of knowing, and that it is possible to have exactly the

same circumstances and attitudes about these circumstances held in a

different context, and that, as a matter of fact, it is possible for people

to choose their own context for the contents of their lives. People

come out of the training 'knowing' that in a new way. Now I mean

something larger than 'knowing' or understanding. I mean that people

experience being empowered or enabled in that respect. They no longer

are their point of view. They have one, and know that the one they

have is the one they chose, until now, and that they can, and

probably will, choose to create other points of view. They experience,

that is, that they are the one who defines the point of view, and not

the reverse. They experience the intended result of the training, which

is a shift in what orients people's being from the attempt to gain

satisfaction - a deficiency orientation - to the expression of

satisfaction already being experienced - a sufficiency orientation.

This is so even for the experience of psychosis. In our research , we

have asked independent investigators to look very carefully at the issue

of harm. And while I am not fully qualified to discuss the intricacies of

research , I can report that none of the research has shown any

evidence that est produces harm. Now, although it has not proven that

est does not harm, it is noteworthy that investigators asked to look

carefully at this question have not found evidence of harm. Every

indication we have suggests that there is a lower incidence of

psychotic episodes either during the training or among the graduates

after the training than in a comparable group.

Interestingly, those graduates of the est training who have experienced

psychotic episodes after the training, report that they experienced the

episode in a different way after the training than when they had such

episodes before the training. For example, in Honolulu, at the general

hospital there, two of the people who had psychotic episodes were

graduates, as were some of the hospital staff. The graduates who had

psychotic episodes said that their experience of psychosis after the

training differed from their experience of it before the training in that

they had somehow gained the ability to complete their experience

rather than manage it or control it, or suppress it. We could say that

they seemed to move to mastery of the psychotic material rather than

be the effect of it. So it would appear that the epistemological shift at

the core of the est training is one which can be used to recontextualize

even psychotic episodes, although they are so rare in our experience

that this tentative generalization must be regarded as based on a very

small sample. We are currently planning systematic controlled research

on this and other issues.

The Epistemology of est

Properly speaking, est is not an epistemology, since epistemologies are

ordinarily defined as ways of understanding the contents of experience,

and est is not about understanding the contents of experience; it is

about the source or

generation of experience. We enter here into a region of discourse

laden with initially baffling paradoxes, since we are dealing now with

understanding understanding, as it were, a task perhaps not unfamiliar

to psychiatry.

What makes est not simply another discipline or epistemology, as far as

I can tell, is what makes relativity and quantum mechanics different

from the disciplines which preceded them and that is that the

disciplines which preceded relativity and quantum mechanics derived

from epistemologies based on the sensorium. What is very clear to me

is that est is not based on the sensorium, so I employ relativity and

quantum mechanics because I need examples of disciplines which do

not derive from sense experience. There are facts in relativity which do

not 'make sense' yet there is a logic in relativity which is as hard and

certain as the epistemology of classical physics, without being based

on sense data, although - in an expanded context - in accord with it,

i.e., allowing and even giving insight into it.

And, just as it is actually impossible to hold the data of relativistic

physics in a classical context, so it is simply impossible to hold the data

of est in the context of classical epistemology. In other words, I am

using words derived from a prior epistemology to describe a later

epistemology that does not fit within the prior epistemology. This is

why a good deal of what I have to say often sounds uncomfortably

paradoxical, and in some views, 'foolish'.

I am saying that what is different about the epistemology of est is that

it moves beyond the sensorium to a reality which, while allowing sense

experience, is not confined within it. It is neither rational, in the usual

conceptual meaning of that term, nor irrational, in the usual emotional

or affective meaning of that term. It is a supra-rational epistemology,

beyond both of these classical alternatives. Just as we cannot reduce

a relativistic space into Cartesian coordinates of x and y, so I hold, we

may not reduce the space from which epistemologies derive, the

context of epistemologies - what I call self - into classical conceptions

of self, the self as a thing or as a point or at best as a process.

I do not mean to be arrogant in citing Einstein as a case in point of

paradoxes of this sort. I do so because he represents the most familiar

example of someone who somehow managed to convey relativity to a

world in which there was no basis for understanding it. He often

referred to the fact that it is theory which tells us what to look for, and

initially put forward his theory without benefit of experimental

verification. Then, when we looked, we found that light rays did bend

on their way around the sun. Somehow, he said what could not be said.

Similarly, in the est training, we say things you cannot say and people

get things you cannot tell them.

Now, this is not really as paradoxical as it sounds, because the truth is,

although you cannot fit an expanded context into a contracted one,

you can fit a contracted context into an expanded one. It is simply the

case that most of us are very reluctant to come up with an expanded

context for our experience, because we think that it invalidates our

previous limited context, and thus presents a threat to what we think

our survival is based on. Now, there is a paradox worth reckoning with,

since, in my view, it is precisely the expansion of limiting contexts

which not only vouchsafes survival but generates those rare

experiences I have referred to as moments of spontaneous

transcendence, or transformation. I mean experiences of self - not self

as concept, or self as peak experience (the experience of self by self) -

but the direct and unmediated experience of self as self, not limited by

previous context. Or, indeed, by any context.

There you have it. For most humans, self is positional - a location in

time and space - a point of view which accumulates all previous

experiences and points of view. You are there and I am here. During

the training there is a shift in the way one defines oneself - not merely

in the way you think about your definition of self - nor merely in the

way you believe your self to be - but in the actual experience of who

you are as the one who defines who you are, not the definition. As self,

you are no longer a content - another thing in the context of things -

but the context in which contexts of things occur. You become a space

in which one of the things, one of the contents is your point of view

about who you are. You are no longer that point of view. You have it,

as one of the experiences you have. You experience you as the one

who is experiencing you.

I know this is an unusual way to use the words self and experience,

and since I have no intention to mystify, let us move towards a

schematic that may be useful in illustrating what I mean.

There is the experience of self as self, the experience of self by self,

and the experience of self as symbol or thing.

If I ask you to describe what you are experiencing right now, almost

everyone who decides to go along at all, without considering whether it

is possible, starts a process in which they try to articulate what they

are experiencing. That we experience is axiomatically assumed by

almost all of us all of the time. It is as though it were a given. (Back in

the 'old days' people may have said something like, 'What I'm

experiencing is that I don't like it in this room. It's terrible. The whole

thing is awful. I just got up on the wrong side of the bed today and

nothing is going to work out.' Today we know better than that. Today

we are hip. We know to describe what we are experiencing in

experiential terms, rather than in conceptual terms.) We might begin

with a description of the perception of our senses; go on to describing

our body sensation; emotions and feelings; attitudes; states of mind,

'mental states'; our fundamental approach to circumstances, and our way of looking at things, i.e., our point of view; we might describe our

motion or movement, kinesthesia; and we might describe the actual

thoughts we are thinking right now; and what we are imagining or

remembering. Let us locate all of these components of experience

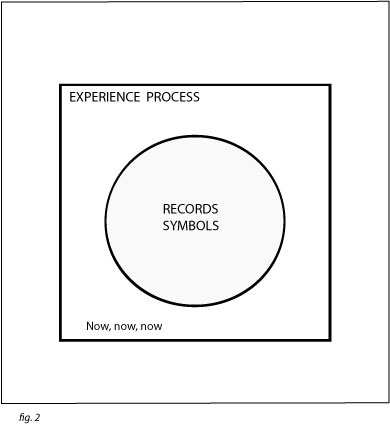

within the square in figure 1.

The square itself represents the instant-by-instant nature of the

experience

of life - not the process, or the accumulation of these instances. The

square stands for now, and then now, and then now.

Of course, when I ask you to describe what you are experiencing right

now, I have actually asked you to do the impossible. By the time you

apprehend your experience - that is to say, when you stop to see or

note what it is that you are experiencing, you are no longer denoting

what you are experiencing now. You are, in fact, denoting what you

experienced a moment ago. Actually, it is more elusive than that,

because experience itself has no quality of persistence. In other words,

what you experienced a moment ago is now gone as experience. What

remains of what you experienced a moment ago is not experience but a

record of what you did experience in that moment (commonly called

memory). In other words, when you stop to formulate what it is you are

experiencing so that you can note it and think about it or realize it or describe it, it is not

only not now, it is not even experience. It is, in fact, merely a record of

what you experienced - a record consisting of a collection of symbols

which you use to represent what you experienced. So the best you can

hope to do when I ask you to describe or take note of what you are

experiencing right now is to describe or take note of the symbols of

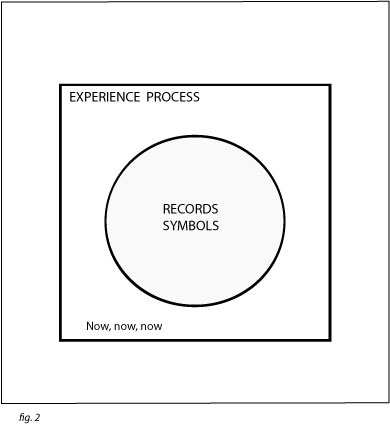

what you experienced a moment ago. These records or symbols of

experience are represented in figure 2 as a circle.

To review: The square represents the instant-by-instant process of

living. It is for the most part unformulated until it is formulated as

symbol in a manner dictated by our concepts and then retained as

concepts. The square represents experience or process. The circle

represents symbols and concepts. The function of the concepts (the

circle) is to organize experience or process (the square). In other

words, the function of concepts is the organization of experience into

meaningful patterns, then groups of patterns and the relationships of

groups of patterns.

For example, if you were to see a ghost walking in front of you, you

probably would not say, 'Terrific, my first ghost'. More likely, you would

say, 'I must have eaten something strange for dinner', or 'Perhaps I

have been hypnotized'. In other words, your mind's concepts will organize the raw experience -that is to say, formulate it (represent or

symbolize it) so that it is consistent with your concepts. If it were not

for this organizing ability, you would grope around your own room to

discover the way out. As a matter of fact, without this organizing

ability even the experience and the resultant idea that there was an

outside of the room would occur only by accidently falling through the

doorway each time you are in a room.

So in the circle we have the organizing principles of experience or the

organizing principles of process or the organizing principles of what we

generally call life. Conversationally, we use the word explaining rather

than organizing, so conversationally, organizing principles become

explanatory principles. Unfortunately, most of us make no distinction for

ourselves between moment-by-moment experiencing and the concepts

which are records and organizations of those experiences.

Our language even uses the same symbol (the word experience) for

these entirely different phenomena. We say, 'I am experiencing talking

to you' and 'I remember the experience of having talked to you'. What I

really remember is the symbols and concept I used to record the

experience of talking to you, and I use the same word for both of

these.

What ordinarily happens is our concepts begin to determine what we

experience. These concept-determined experiences (mechanicalized

experiences) then reinforce the concepts from which they arose, which

reinforced concepts further determine experience, and so on. In this

conceptualized or mechanicalized condition of living, one is at best

successful and at worst a failure or pathological.

As far as I can tell, when we said something was 'wrong' with people,

what we have often attempted to do in our society was to get them to

give up `bad' concepts or take on 'good' concepts. In modern

therapies, we now attempt to break the hold of concepts on experience

so that people can be more directly aware of their experience and

experience more directly.

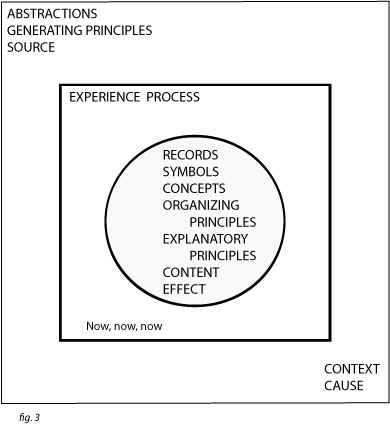

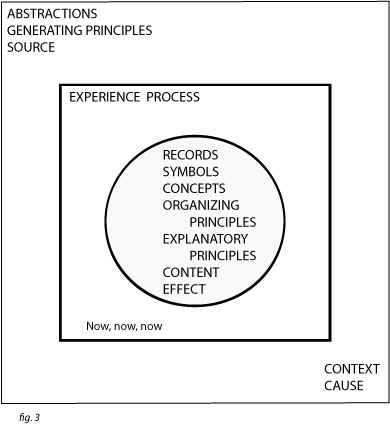

I am suggesting a third possibility, beyond experience or process and

beyond symbol or concept. The third possibility is represented in figure

3 by the space in which the square and circle are drawn on the page.

In other words, it is the page itself. This space of the diagram

represents what I call a generating principle - that which gives rise to

experience, as distinguished from experience/process, or the

organization/explanation of experience. It is the source or creation or

generation of experience or process or, if you will, life. Rather than

organizing or explaining, it generates or creates. And rather than being

conceptual and symbolic, it is abstract.

In Zen, they say that those who know don't tell. What they may mean

is that self as self (represented by the space of the diagram) generates

experience, sources life. It does not explain it or 'organize' it. In Zen,

they also say that those who tell don't know. What they mean is that

self as symbol or thing (represented by the circle in the diagram) can

explain it but cannot source or generate it. We all know people who can

explain and rationalize their entire lives and everyone else's, for that

matter, who do not generate real satisfaction, fulfillment or aliveness in

life. At best they present a good facade.

Traditionally, the world is usually divided into two groups: people who

are experiential or intuitive or feeling or emotional or non-rational and the

other camp, people who are intellectual, verbal, conceptual and

rational. I am suggesting a third possibility which requires a new

paradigm of understanding and a logic, philosophy, language and syntax

which are appropriate to it. To point in the direction of what I mean

here, I use the analogy of relativity and quantum mechanics, which

required physics to generate a new paradigm not understandable in the

old classical paradigm, but which is a state change or, as I prefer to

call it, a transformation. Relativity and quantum mechanics also require

a new logic, philosophy, language and syntax of the physicist, which in

the old logic, philosophy, language and syntax sound paradoxical and

irrational - but once apprehended are seen to be fully logical, rational

and consistent and even allow the old logic, philosophy, language and

syntax - perhaps even illuminate it. This is not anti-intellectual or

irrational or even non-rational. It is a kind of supra-rationality, a

context in context.

The difficulty I have with the prevailing scientific epistemology is that it

tends to move backwards - from content to context (from the circle to

the square) which in my view forces us to locate the source of

experience in the result of experience.

I suggest there is another way and that is, to come from the source of

experience - which has a logic all in its own - to experience - which too

has a logic - and move on to the symbolic record of experience - which

also has a logic, or order all its own.

What we ordinarily call logic is actually a specialized logic which is

consistent with a symbolized and conceptualized sense-perceived

reality. It is the logic of content, object or thing - a logic of, reality of

parts. There is another, separate and distinct logic which is consistent

with a process (experiential-here-and-now) based reality. It could be

said that this logic is consistent with a sense-perceived reality which

has not been symbolized and conceptualized. Actually, the reality with

which this logic is consistent includes - in addition to sense perception

- such items as body sensation, emotion, feeling, attitude, state of

mind, movement, motion, kinesthetic, thought itself, imagination, and

memory. An example of this is the logic of art, dance and music which,

by the way, often appears illogical and irrational when seen from the

logic of the symbolized and conceptualized sense-perceived reality. (It

is a fundamental malady in our culture that as we become more

enculturated we become more likely to try to make sense out of our

experience-process with a logic of symbols and concepts.)

While the first of these two logics does not include the second, the

second includes the first. That is, the second one is the context for the

first one.

There is a third logic which is distinct and separate from the first and/or

second of these two logics. It is even further removed from what we

ordinarily call logic, and, as a matter of fact, it seems completely

paradoxical, non-sensical and strange when viewed from the

perspective or ordinary logics. It is a logic which is consistent with a

source-of-form rather than form - source-of-time rather than time -

source-of-position rather than position-based reality. It is the logic of

context and creation - a logic of a reality of wholes. It is a logic of

universals, of ultimate contexts, which allows for process, change,

experience, and particular sets of contents.

This logic system of self as self is not 'sensible'. It seems paradoxical,

because it must speak a language based on a logic of the senses, in

which the subject of the verb must be different from the object of the

verb. Self as self does not 'make sense'.

Self as self is represented in figure 3 as the space or content of the

diagram. The experience of self by self is represented by the square in

the diagram. Self represented as symbol, or self experienced as an

object or thing, is represented by the circle in the diagram. Self as self

does not explain behavior, it generates it. Self as concept does not

generate life - it only explains it. Generating principles generate and

explaining principles explain.

This brings us to the final notion I want to present in this essay - the

notion of responsibility. In ordinary discourse, I find the idea of

responsibility almost totally buried under concepts of fault, guilt,

shame, burden, and blame, so that a discussion of responsibility almost

invariably elicits a defensive response, as if to say, 'it wasn't my fault',

or a brave, 'I did it'.

And yet, the experience of responsibility for one's own experience is the awareness that I am the source of my experience. It is absolutely

inseparable from the experience of satisfaction. Satisfaction is the

natural concomitant of the experience of self as generating principle or

abstraction or source or cause. Only if I love you do I love you, and if I

am not responsible for (the source of) loving you - then 'obviously', I

am not loving you. I might have love for you or do love for you but I am

not loving you. Having or doing love can be gratifying, need-fulfilling,

and cannot be satisfying, whole or complete.

Similarly, if I am not responsible for (the source of, the cause of) my

experience of the predicaments in my life, then I can only resist, fix,

change, give into, win out over, or dominate. Paradoxically, the

experience of helplessness or dominance results from the attempt to

locate responsibility outside of self and sets up a closed system out of

which it is sometimes very difficult to extricate a valid experience of

self; since the self which might otherwise be responsible has been

excluded in the attempt to protect it from guilt, shame, blame, burden

and fault.

I am sometimes asked whether I 'really' mean that people are wholly

responsible for their experience of life, as if I wished to blame people in

poor circumstances. For example, I am asked whether accident victims

are 'responsible' for having accidents. I hope it has become clear in the

context I have developed above that such questions might involve an

oversimplification.

Responsibility, in my view, is simply the awareness that my universe

of experience is my own including the experiences of those events in my

life I call accidents.

Responsibility begins with the willingness to acknowledge that my self is

the source of my experience of my circumstances. And yet, on

occasion, some people think that I think accidents do not happen - or

would not happen, if I were 'really' responsible. I am sure you will

understand my occasional dismay when I am asked questions of this

sort. On reflection, I usually recall that such questions derive from a

well-intentioned (though perhaps limited) view of human dignity, an

intention with which I can align myself, since my own intention is

precisely to show that the experience of responsibility is enabling, not

disabling.

I have no interest in the justification of circumstances or producing

guilt in others by assigning obligation. I am interested in providing an

opportunity for people to experience mastery in the matter of their own

lives and the experience of satisfaction, fulfillment, and aliveness.

These are a function of the self as context rather than thing, the self

as space rather than location or position, the self as cause rather than

self at effect.

I am not saying that you or anyone else is responsible. True

responsibility cannot be assigned from outside the self by someone else

or as a conclusion or belief derived from a system of concepts. I do not

say that you or anyone is responsible. I do say - with me, you have the

space to experience yourself as responsible - as cause in the matter of

your own life. I will interact with you from my experience that you are

responsible - that you are cause in your own life and you can count on

me for respect and support as I am clear that I am fully responsible for

my experience of you, that is to say, from my experience of the way

you are.

Ultimately, one experiences oneself as the space in which one is and

others are. I call this the transformation of experience. At the level of

source - or context - or abstraction - I am you. That is beyond

responsibility.

In sum, I affirm that human experience is usually though not necessarily

ensnared in a trap of its own devising, born of a wish to survive and

remain innocent. And ironically, our stubborn wish to survive prompts us

to rely on concepts of life built with records of past survivals, thus

reducing self to victim, or at best to survivor or dominator, on which

spectrum, every position is one of effect.

Werner Erhard

Victor Gioscia, PhD, Director of Research and Development

ERHARD SEMINARS TRAINING LINKS:

Erhard Seminars Training - Internet Archive

Erhard Seminars Training - Financial Times 2012

Erhard Seminars Training - New York Times 2015

The est Training Website

|